FROM PERSIA TO KASHMIR, AN HEIRLOOM OF ORNATE CRAFT

The art of Kashmiri carpet weaving is famous for its elegant Persian motifs, stitched by hand in warm colors on silk and wool. Carpet variations in Kashmir also include gabbas, namdas and chain stitched wool rugs. Other notable handicrafts include jewelry, silk fabrics, silverware, and woollen fabrics like Patti (milled blankets) and Patto (tweed).

Mapping the Introductory Steps of Persia in Kashmir

Tracing the evolution of Kashmiri craftsmanship, the biggest catalyst of Kashmiri art, for what it is today, is credited to Iran, Central Asia, and local influences, guided by key historical figures.

The pioneer who introduced Persian elements in Kashmir back in [d.1327] was Bulbul Shah, laying the foundation for Iran’s rich heritage to flow into the valley. Shortly after, in 1339, the Shahmiri dynasty was founded by Shams-ud-Din Shah Mir, which marked the initial checkpoint of structured patronage for Persian-inspired art, including calligraphy, wood carving, and early shawl weaving.

Then, in 8 Hijri, the first major influence and beloved saint who traveled to Kashmir was Hazrat Mir Syed Ali Hamadani, accompanied by the Iranian Sadat families. Introducing revolutionary changes in the civilisation, culture, and religious aspects of Kashmir, Mir Syed Ali Hamadani traveled with highly skilled Iranian men and 700 artisans who introduced the art of carving, mosaic work, samovar making, carpet designing, and cloth making. As a result, Kashmiri culture underwent a major reset. He also brought different seeds of fruits and trees from Iran and Afghanistan, including lily and hyacinth. Moreover, he introduced changes in Kashmiri attire, including the famous Iranian shirt.

As a result, architecture, painting, calligraphy, the carpet industry, fabrics, and textile designing in Kashmir were deeply influenced by Iranian artistry. He also introduced industries from Hamadan (Iran) most notably the shawl industry (Javādī, 1991).

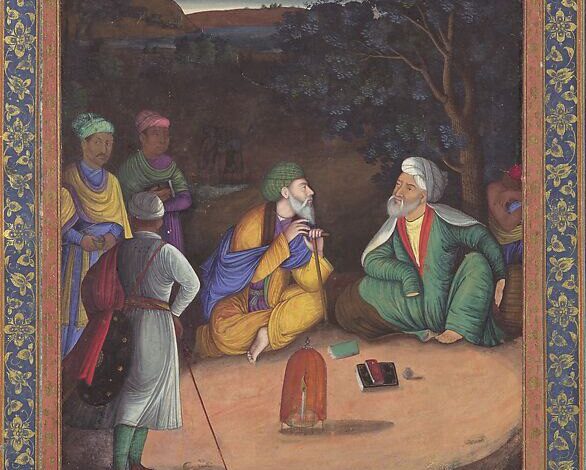

Hereafter, Kashmiri art and craft flourished, and during the Mughal period, Kashmiri textile designs were used in miniature paintings to depict their beauty. According to Brown (1924, p. 189) Kashmiri painters would achieve a delicate effect by allowing water to evaporate completely, leaving behind a sediment that created a faint yet a beautiful charming contrast between the flesh tones and the background.

Ali Hamadani believed that making the youth dependent on charity would turn them into parasites. Therefore, he introduced craftsmanship and made the Kashmiri youth self-dependent, which he considered to be a form of prayer. Hence, by promoting Iranian arts and crafts, Mir Syed Ali Hamadani transformed Kashmir into Iran-e-Sagir (Little Iran).

Hence, Persian arts and crafts didn’t just become an innate part of Kashmiri tradition but also laid the foundations for its textile, architectural, and artistic heritage. Even today Persian inspired designs and motifs are observed to be embedded in Kashmiri culture, making it a legacy of Iran’s artistic impact.

The intricate Art Of Carpet Weaving And Kashmiri Handicrafts

The monumental influence that acted as a guide for Kashmiri carpet weaving was the Iranian Safavid dynasty (1501–1722) that also elevated the art of carpet weaving in Iran. Cities like Tabriz, Qazvin, and Isfahan ended up becoming centers of production with patronage from rulers such as Shah Ismail I (1501–1524) and Shah Abbas I (1571–1629) (Razavi, 2018). There’s still some debate of the origins of Safavid carpets with some attributing their designs to the Timurid era (Rene, 1912) and others tracing them to the Kara Koyunlu and Aq Qoyunlu dynasties (Nasiry, 1995). Regardless, Safavid carpets set a high standard in craftsmanship, which later influenced Kashmiri rug-making.

The art of Kashmiri carpet weaving is famous for its elegant Persian motifs, stitched by hand in warm colors on silk and wool. Carpet variations in Kashmir also include gabbas, namdas and chain stitched wool rugs. Other notable handicrafts include jewelry, silk fabrics, silverware, and woollen fabrics like Patti (milled blankets) and Patto (tweed). The legacy of Persian carpet weaving continues in Kashmir today with designs being an artistic memoir of Safavid masterpieces.

Kashmiri Shawls And Persia : A Cross Knit

The word shawl is derived from the Persian word shal which originally stood for a category of woven fabric rather than a specific dress item. In Indo Persian tradition, this term also applied to mantles, turbans, and scarves, with the standout attribute being the delicate animal fleece or fine wool. The famous delicate brocaded woollen shawls of modern times very closely resemble those of Kashmir. The origin of brocade weaving in Kashmir is hard to specify but local legends pin it around the early 19th century (Hogel, 1845) attribute it to Zain-ul-Abidin. It is said he brought Turkistan weavers to establish the industry.

Kashmiri woollen shawls are renowned for their intricate embroidery work, varying in price depending on wool quality and embroidery technique. The raffel wool woven in Kashmir is 100% pure, although sometimes blended with cotton or cashmilon before the embroidery is done. The beautiful needlework, or Sozni, is the most common form of embroidery found along the shawl’s edges. The traditional material for Kashmiri shawl weaving came from the Capra hircus, a Central Asian mountain goat. In the West, this wool was popularised as cashmere, named after Kashmir.

During the early Mughal era some shawls were decorated with silver and pure gold thread. Manrique (1927) describes the finest pieces as having “outskirts ornamented with gold fringes, silk, and silver thread,” worn by nobles as capes and shrouds. Around the 19th century, Kashmiri shawls became a symbol of prestige in affluent households. Over time, they were passed down generations and preserved as heirlooms. Women would wrap these around their waists or wear them like turbans around their heads. The shawl industry especially flourished during the Sultanate period, making Kashmir a mini Bukhara and Samarkand.

There is also multiple evidence suggesting the export of Kashmiri shawls to Iran. The earliest visual evidence is found in paintings from the late 18th century, where distinct patterns such as Both and Khakras are beautifully depicted on garments.

Persian Influence on Kashmiri Calligraphy and Architecture

Following the arrival of Persian culture, calligraphy flourished in Kashmir, and the Persian script became the dominant form of writing. Persian calligraphy styles such as Nasta’liq, Thuluth, and Kufic were introduced, transforming both religious and literary expressions. The earliest Persian inscriptions in Kashmir can be dated back to the Shah Mir dynasty, which officially ended up adopting Persian as the court language of Kashmir.

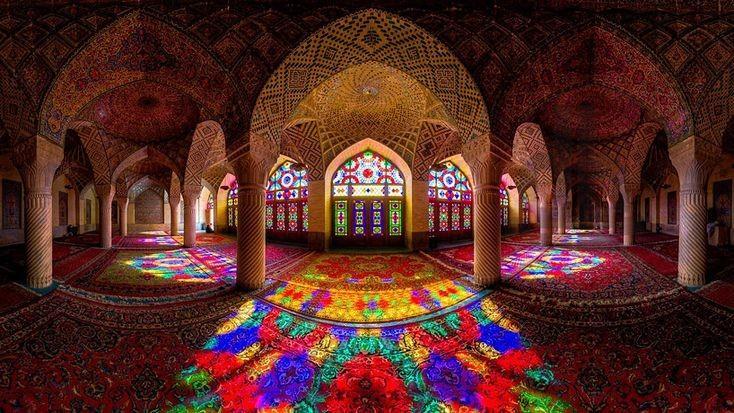

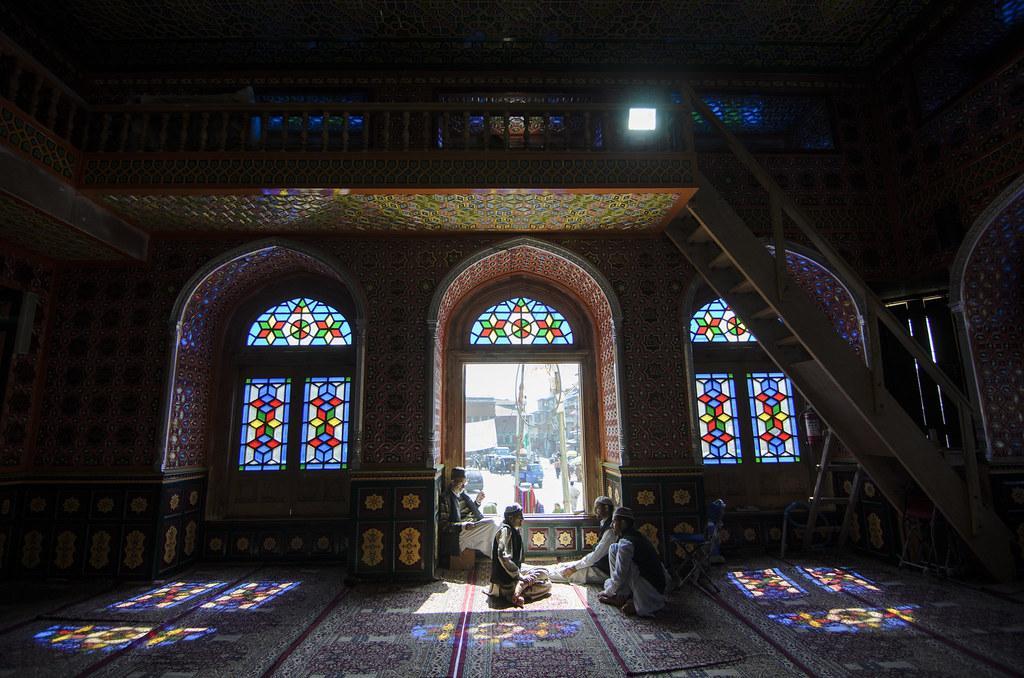

Persian influence on Kashmiri calligraphy is evident in Kashmiri architecture, particularly in mosques, shrines, and the local madrasas. Some of the most prominent examples of Persian architectural influence in Kashmir include:

– Shah Hamadan’s Shrine (Khanqah-e-Moula): This ethereal shrine features Iranian woodwork, geometric patterns, and intricate papier mache designs.

– Jama Masjid, Srinagar: This mosque was built by Sultan Sikandar and later expanded by Zain-ul-Abidin, exhibits a Person-Central Asian architectural style including wooden pillars and beautiful Persian calligraphy.

– Tomb of Zain-ul-Abidin’s Mother: Reflective of Persian dome structures and their distinct tile work, the architecture is reminiscent of Iranian mausoleums.

The influence of Persian architecture in Kashmir is also observed in the wood-carved ceilings, brickwork, and floral motifs which are still actively used in Kashmiri structures today.

(A comparison of the two most famous shrines in Iran and Kashmir, the motifs to the woodwork and glass mosaics, stand reflective of the similarities between the craftsmanship of Persia and Kashmir.)

Papier-Mâché and Woodwork: Gifts from Persia

One of the most exquisite Persian influences in Kashmir is papier mache, locally known as Kari-Qalamdani This was introduced by Persian artisans and is still considered to be one of the most treasured and respected art forms in Kashmir today.

Papier mâché involves:

1. A handmade paper pulp molded into delicate shapes that are popularized as decor.

2. This model is then covered with intricate Persian inspired designs, including floral motifs, paisleys, and arabesques.

3. All of this is topped with gold and silver work which adds a luxurious luminous touch of quality to the artwork.

Wood carving in Kashmir reflects the deep influence of Persian craftsmanship. The detailed latticework and geometric patterns on walnut wood come from Persian traditions, passed down through generations.

Iranian art and craft has shaped Kashmir in many ways, showing the long history of cultural exchange between the two regions. From the delicate thread of shawls to the very architectural bricks from the strokes of calligraphy, Persian craftsmanship has shaped the Kashmiri artistry for generations. The values of Mir Syed Ali Hamadani and his followers continue to inspire life into these traditions, making them an inseparable part of Kashmir’s culture and traditions.

Even today, the soul of Persian aesthetics carries on in Kashmiri designs, poetry, language, and artistic expressions. It is woven into the valley’s identity, etched into its art, and whispered through its snow clad mountains a beautiful pashmina thread between the past and present.